Life on The Avenue

John Finley Jr. is buried next to his wife, Evelyn Franklin Finley, in Oaklawn Cemetery. The single headstone, inscribed with crosses and flowers, simply gives the years they died. John passed away in 2002. Evelyn died 18 years before in 1984.

There’s no mention of Finley’s Pharmacy No. 1, the store John opened in 1950 on Davis Avenue that became the hub of a thriving Black community.

There’s no mention of the rooms in the back, where Black doctors started their practices or the soda fountain where kids lined up for ice cream every day after school.

There’s no mention of “the book,” which contained a list of customers who purchased their prescriptions on credit because John Finley refused to turn anyone away.

“Davis Avenue was vibrant through the 1960s, and my dad’s store became like the Chamber of Commerce, where people of all walks of life came in and talked about the community,” said the Finleys’ youngest son, Eric. “It was a time where a handshake and looking a person in the eye meant something.”

Davis Avenue, named after the President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, was called The Avenue by locals. It was the center of business, shopping, socializing and entertainment for Black Mobilians who were unwelcome in many other parts of the city.

People on The Avenue traded garden vegetables for car repairs or eggs for doctor visits. Women opened restaurants and beauty salons. Girls tried on hats at Stella’s Hat Shop. Skilled laborers helped build neighbor’s homes, and children roller skated down Blueberry Hill.

They were proud of Central High School and its band, The Marching 130.

Some had no money or education and came to find work beyond the cotton fields of Alabama.

They were a people without the right to vote or access to bank loans, but they built power with the dollars they earned.

Created by segregation and the laws of the Jim Crow South, Davis Avenue became a prosperous district that represented achievement.

The Avenue was a 2-mile stretch from the International Longshoremen's Association Hall, close to downtown, to the former Roger Williams Housing Project across Three Mile Creek.

There were four movie theaters, grocery stores, funeral parlors, churches, barbershops, hairdressers, tailors, restaurants, grills and hot dog stands. There were also pool halls, record stores, taverns, social clubs, pawnshops, cleaners, appliance stores, bakeries and a cigar-maker. They weren’t all Black-owned businesses, but all of them welcomed Black customers.

Photo from the University of South Alabama

Black folks from other areas took the bus to Bienville Square then caught the transfer to Davis Avenue. Old photos of The Avenue show a street filled with Pontiac Chieftains, Chevy Stylelines and Bel Airs.

There are memories of Watermelon Man and Vegetable Man, who sold fruit and produce from the back of their trucks, baseball player Jackie Robinson and Henry “Dunn by Nunn” Nunn, a former Mr. America bodybuilder who painted murals on store walls.

It was a place where children played hopscotch and jacks. They got into the movies for free with labels from cans or for reciting the Ten Commandments.

It was where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made his only appearance in Mobile, preaching on non-bitterness and love. On January 1, 1959, King told the packed crowd in the ILA Hall that “the old order of segregation is passing away, and a new order of freedom is just coming into being.”

The ILA Hall was also the place for dances and Mardi Gras balls. It was a favorite on the street, described as “always alive.”

Original piano still onstage at the ILA Hall.

Local musicians have said there were 20 clubs along The Avenue. With names including The Ponderosa, The Ebony Club, The LeSabre Club and the Bonita Lounge, the clubs and auditoriums were where Fats Domino, Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Charles, The Drifters, Cab Calloway and Nat King Cole played.

“The Avenue was our Harlem,” said Eric Finley. “But if you didn’t experience The Avenue, it’s hard to imagine what it used to be. It was renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue in 1986 and almost nothing remains.”

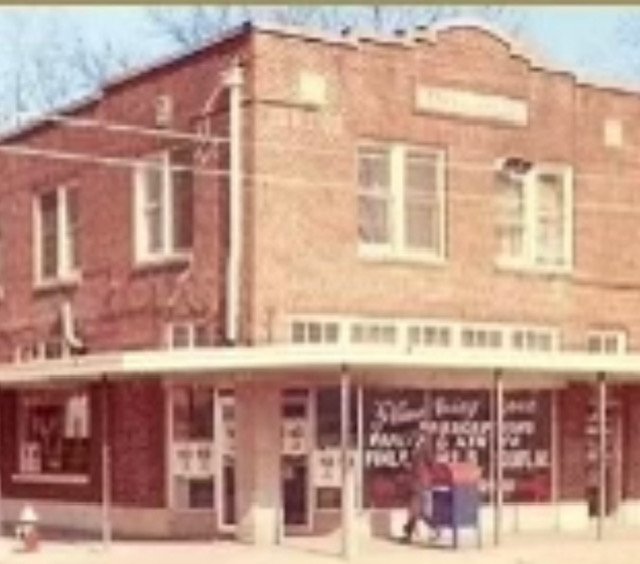

John Finley Sr. opened Finley’s Pharmacy No. 1 between Patton and Belsar Streets, and it’s one of the few buildings from the Davis Avenue era still standing. Next door is an empty lot, where the Booker T. Washington Theater used to be.

Dad opened the store at 8 a.m. and wouldn't close until 10 p.m.,” said Eric Finley who worked at the drug store after school and during the summers. “People still rattled the door after that. He and Dr. Maynard Foster made house calls in rural areas to people who didn't have transportation.”

Eric’s older brother, John Finley III, a retired pharmacist who worked with their father, said he “had a big heart and couldn’t turn anyone away. Sometimes he allowed a customer to pawn a ring or knife for a prescription.

“Our father understood what they were going through because he grew up during the Depression,” he said. “His family lived in the Bottom, a neighborhood off Davis Avenue. Their house was next to the dump, and they never forgot where they came from.”

Robert Rembert, the last original barber left on The Avenue

Across the street from the Finley’s Pharmacy building is Rembert’s Barbershop, one of the few original businesses still open. The owner, Robert Rembert Sr., was one of the first graduates of White’s Barber College, the first barber college in Alabama. Isaac White Sr. opened the school on Davis Avenue in 1960. He not only taught men a trade but refunded their tuition after graduation.

“I worked for Mr. White for two years,” Rembert said. “I am 80 and the only original barber left on The Avenue.”

Rembert once worked at Moody’s Barbershop, down the street from the Le Grand Motel. Its matchbook cover said “Mobile’s Only Negro Motel,” and it was located on 1461 Davis Avenue at Lafayette.

“The Black musicians from Motown toured by bus, and Mobile was a stop along the ‘Chitlin Circuit’ in the South,” Rembert said. “They stayed at the Le Grand or in private homes because the other hotels wouldn’t let Blacks in, no matter how famous they were.”

Rembert watched stars such as Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Little Willie John and Hank Ballard walk from the motel down The Avenue. He said they often popped in to play The Baby Grand Club across from the motel.

“They also stopped at Moody’s to get their haircut or to talk and play checkers,” he said. “It was nothing to see James Brown, The Temptations or the Four Tops walking along the street or shopping for toothpaste or hair products in the drugstores.

“On Dauphin Street, we had to step off of the sidewalk when a white person passed, but everyone was welcome and respected on The Avenue,” Rembert said. “I wish I had taken pictures. They would be valuable today.”

Davis Avenue started out as a dirt trail in 1800 or so, connecting downtown to the northwest. The path cut through a 540-acre parcel owned by William Kennedy, a local physician loyal to Spain.

In the 1830s, the trail was named Stone Street Road after settler Sardine Stone. Thirty years later, the area became a campground for Confederate troops, and the road was renamed after Jefferson Davis. A Confederate gunpowder magazine still stands close to Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue.

After the war, the Freedmen's Bureau helped freed slaves settle in the area known as “The Campground.” Black folks also moved in from rural Alabama to get dock and factory jobs in Mobile.

Paulette Horton’s book, “The Avenue,” tells the story of the street, the people and the memories from 1799 until 1986.

The Avenue by Paulette Davis-Horton

“When I started the interviews in 1988, people didn’t think the history of Davis Avenue was important,” Horton said. “The young people under 30 didn’t even know it existed. Unfortunately, almost everyone I interviewed has passed away.”

Part of that history was the people who lived on the city dump, several blocks north of Davis Avenue.

Starting in the early 1900s people came to Mobile with no place to live, Horton said. Hundreds of them built homes on the dump using tar paper, cardboard, tin and pieces of wood.

“They survived on what the garbage trucks brought in,” she said. “They cooked food over a fire and sold the metal, paper and glass.

“Some dressed up at night and went to Davis Avenue to have fun.”

Horton also wrote about the merchants on The Avenue, including poor European peddlers who immigrated to Mobile. They opened stores on Davis Avenue because it was a good place to make a living.

One of those was Jay Bee’s Variety Store, located between Pearl and Cherry streets and owned by J.B. Friedlander.

“The sales at Jay Bee’s were a big deal,” said Donnie Friedlander, J.B’s son, who worked at the store as a teenager. “Sales banners hung inside and outside the store. We put a rooster or chicken in the window and had a contest to see who could guess how many kernels of corn it could pick up. The correct guesser won the door prize. The store was packed at the sales.”

People cashed their checks on Fridays at Jay Bee’s and paid off the cigarettes, shoes or work clothes they purchased during the week, Friedlander said. That was before credit cards, when purchases were often made on trust.

“Dad only charged 25 or 50 cents to cash a check,” said Friedlander, who is now a lawyer in Mobile. “That was nothing compared to the check cashing companies. He kept an index box with what they charged.”

These days, Eric Finley leads tours for the Dora Franklin Finley African American Heritage Trail and drives along the former Davis Avenue pointing out where stores such as Jay Bee’s used to be.

He stopped in front of a parking lot and vacant field of grass, describing the businesses once there in the heart of Davis Avenue. One was a two-story brick building on the corner lot, built by Dr. James Franklin.

“Dr. Franklin built his practice along The Avenue, giving his patients the best possible care, whether they could pay or not,” Finley said. “He worked 12-hour days, sometimes seeing 100 patients a day, and never raised his rate during his 60 years of practice. On his gravestone is the inscription ‘Debts due me, paid in full’.”

Eric’s mother, Evelyn, was one of Dr. Franklin’s 10 children.

“My grandfather pawned his watch to build this building,” Finley said. “It was one of the biggest on The Avenue, and his name was at the top. It was hard on him when they tore his building down during urban renewal.”

The Franklin Building, Photo courtesy of Eric Finley

Finley described the Franklin Building as a mecca for African-American professionals.

“My uncle’s drug store, Finley No. 3, occupied the bottom floor,” he said. “My grandfather’s office was on the top floor; along with the offices of John LeFlore, President of Mobile’s NAACP; attorney Vernon Crawford, who worked most civil rights cases in Mobile; CPA T.N. Reed and Dr. P.W. Goode, a dentist.”

Photo from The University of South Alabama

In the next blocks were the Pike and Lincoln theaters, Jim’s Barbeque and Gomez Auditorium. Across the street were the Besteda Brothers, professional tailors who made suits for many men in Mobile. Their ad in the Mobile Beacon said, “The fit is the thing.”

That shop was open for 57 years before it closed in 1984.

“That was a happening part of The Avenue,” said Eddie Irby, who also grew up in the Bottom.

“We took our pants to Besteda’s for alterations and shot pool next door or ate Babe’s hot dogs while we waited,” Irby said.

Babe's Hotdog Stand was reputed to have served the best hot dogs in Mobile.

“The hot dogs were one for 15 cents or two for a quarter,” Irby said. “Girls put them in their pocketbooks to sneak them into the Lincoln Theater. The guys tried to put them in our pockets. Dead Man worked inside the theater and walked the floor. If he caught you with a hot dog, he made you take it outside and eat it.

“We called him Dead Man because he was jet black and acted like he would kill us on the spot if we disobeyed his orders,” Irby said.

He also said the men on The Avenue watched out for the younger guys.

“They bought us shoes or gave us advice,” Irby said. “They got on us when we were getting into trouble. If we tried to enter the pool hall after dark or peek in the clubs, they ran us off.”

Alfred Johnson sang blues and rock ‘n’ roll in some of the clubs on The Avenue. He got his start at the King Club talent shows in 1957 when he was 15.

Alfred Johnson sang at clubs on The Avenue

“I sang at the Flame Club, the Jolly Spot, the Brown Dot, the Moonlight and the Kool Kat Club,” he said.

“Mobile was popping,” Johnson said. “Most clubs were open 24 hours, and they were making good money.”

Johnson sang five nights a week, making $15 a night. He wore suits that were black and red, yellow and blue or black with yellow pockets. A few still hang in his closet.

The band usually started about 9 p.m., and he went on at 10.

“We played until 2 or 3 in the morning,” he said. “Some clubs were packed out with more than 200 people.

“There was good music everywhere,” he said. “Etta James, B.B. King and Sam Cooke all played here. White people came in, and we had a good time.”

Johnson turns 80 next year. He doesn’t sing anymore, and he misses his days on The Avenue.

“Things died down when the younger generation came in and messed it up,” he said. “No one took over the clubs, and most of them were torn down.”

One of those clubs was The Wilder Place, owned by Nathaniel “Snook” Wilder. His son, Charles, grew up cleaning, stocking boxes and taking out the trash at the club, also known as “Snook’s Place.”

Charles Wilder (right)

“People dressed sharp as a tack on The Avenue,” Wilder said. “They had a nice time and danced to music on the Rock-Ola, our jukebox. The street was so lit up with neon lights that we called it Little New York. There was money made here.

“Today’s Black community is too young to remember how everyone looked out for one another and shared,” he said. “If someone had a problem, they came to my dad. He used his connections and helped people any way he could.”

Nathaniel Wilder is buried at Oaklawn Cemetery with the name “Snook” on his headstone.

“Half of the people buried at Oaklawn were powerful folks,” Wilder said. “The funeral processions went up Davis Avenue to the cemetery. When people saw it pass, they stopped what they were doing and took off their hats, no matter who it was. It was respectful.”

Birdie Brown is also buried at Oaklawn. She couldn’t read or write when she moved from Wilcox County to Mobile, but she made a living with rental properties. She started with two apartments in the back of her house on Dearborn Street, just off Davis Avenue.

“She told people, ‘If you need a place to stay, come see me,’” said her grandson, Caudrey Gray.

Caudrey Gray

“My grandmother made sure my mother and all of us could read and write,” said Gray, who still lives in his grandmother’s home. “We were the only ones with the World Book encyclopedias, so all of the kids in the neighborhood came to our house.”

Gray’s mother made him take piano lessons. He once played for Fats Domino when the singer stayed at the home of his piano teacher, Odile Pope Owen, who lived in the yellow house across the street.

“My brother and I played a duet in the hallway, and Fats listened to us from the kitchen,” Gray said. “I also met Jerry Butler from The Impressions over there. I still have their autographs.”

The yellow house belonged to Owen’s mother, Emma Jordan Ezell, and was listed in the 1949 edition of “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” the guidebook that listed accommodations, restaurants and gas stations across the country that were safe for Black travelers.

“Aretha Franklin was 16 when she came to town with her father and stayed with us,” Ezell’s granddaughter, Brenda Owen Norwood said. “He (Franklin’s father) was a pastor and had quite a ministry.”

Norwood still lives in her grandmother’s house. In the living room on the baby grand piano are photos of the musical family, including her great-grandfather John A. Pope, founder of the Excelsior Band.

Odile Owen started The Pope sisters, known as The Pope Sisters from Mobile, Alabama. They toured the country and performed in movie shorts and on Broadway. Odile and her husband owned the Streamline Cafe, where she often performed, and a dry cleaners. Neither building exists today.

“When they tore down the homes and buildings around Davis Avenue, they tore down our history,” Norwood said. “There is little left for the next generations to learn from.”

Eric Finley said Davis Avenue and those who created it should be remembered. He quoted these words from the top of his tour’s brochure: “We need to listen to their struggles, feel their determination, recognize their courage and celebrate their accomplishments.”

“With nothing left to see,” he said, “it is hard to catch Davis Avenue’s glory, but it lives on in memories and stories.”

Here is a sound track to some of the songs likely played on The Avenue.”

This story originally ran in Lagniappe in December 2021